St. Olaf Latin Play MMV

Click here to download a slideshow from the 2005 production of Plautus’ Curculio.

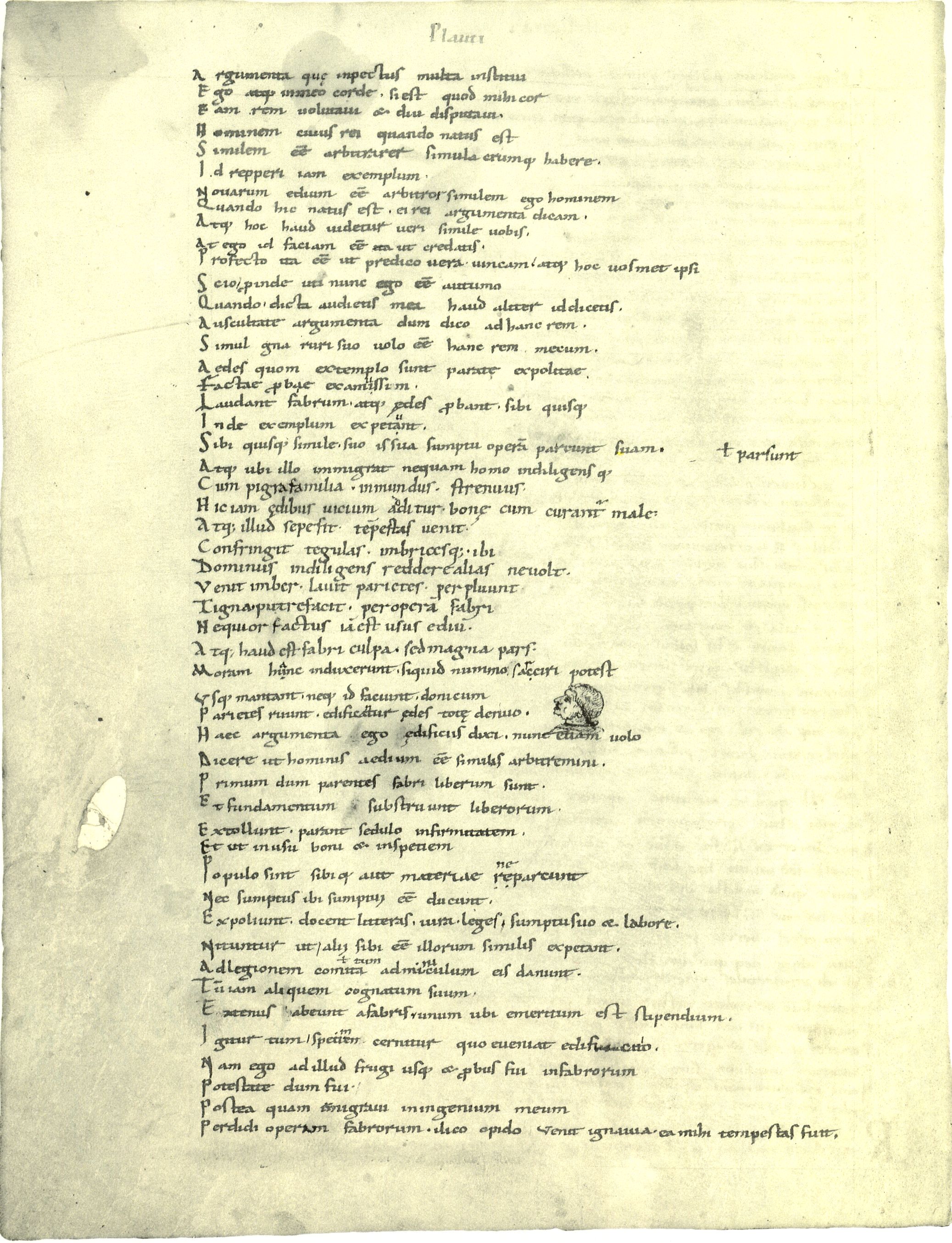

Titus Maccius Plautus (c. 254-184 B.C.) wrote over 100 comedies, of which 20 survive. All are adaptations of earlier Greek comedies. Thus, even though the characters speak in Latin, they are meant to be Greeks, not Romans, and they wear Greek clothing. Plautus’ source for the Curculio is unknown.

The Brothers Menaechmus Summary and Study Guide. Thanks for exploring this SuperSummary Study Guide of “The Brothers Menaechmus” by Plautus. A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality study guides that feature detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, quotes, and essay topics. As an outsider, Plautus has no investment in young love that leads to marriage and the creation of new citizen families. He focuses on stage comedy and the clever slave rather than romantic and sentimental melodrama. He often drastically changes the plots of his Greek originals by removing either the arrangement or the announcement of.

The play takes place in Epidaurus, Greece, at the sanctuary of Aesculapius (or Asklepios, as the Greeks called him), the god of medicine. People suffering from illness used to travel to Epidaurus and spend the night “incubating” in the god’s temple, hoping that Aesculapius or his sacred snakes would appear to them in a dream and cure them.

Curculio is the Latin word for “weevil,” a beetle whose larva eats many times its weight in grain. It is also the name of a major character in the play: the parasite. Like a weevil, Curculio loves food and is willing to do practically anything to earn a meal.

All Greek and Roman drama is written in verse, some of it designed to be sung. In Plautus’ day, accompaniment would have been provided by an aulos, a double-reed instrument similar to an oboe. We set five sections of the Curculio to music, using rhythms that approximate the various meters in which the play is composed.

While we generally remained faithful to Plautus’ text, we took the liberty of adding a chorus of nurses who work for Cappadox. Their song comes at a point in the play where Plautus has the stage manager appear and chat with the Roman audience. We also quadrupled the number of prophetic chefs and added four singing apprentices, as well as a prologue spoken by Aesculapius.

Plautus’ actors would all have been males and would probably have worn masks. The Curculio would have been performed without intermission, as we too performed it.

Scene 1: During Aesculapius’ prologue Phaedromus walks out of his house, followed by Palinurus, his smart-aleck slave. Palinurus

wonders why his master is awake before dawn. Phaedromus reveals that he is in love with Planesium, a beautiful slave-girl living in the house of Cappadox the slave-dealer. Because he has no money with which to buy her freedom, Phaedromus has sent Curculio to Caria (in Asia Minor) to borrow money from one of Phaedromus’ friends. Although Cappadox will not allow the young man to visit Planesium until he can afford to buy her, Phaedromus can’t wait: he has brought along a drink (wine in Plautus’ version) with which to bribe the old woman, Leaena, who guards Cappadox’s door.

Scenes 2-3: Leaena, trailed by her apprentices, is lured outside by the drink’s aroma and sings about her love for that divine beverage (Song #1). Phaedromus asks her to bring Planesium to him for a quick visit. While she fetches the girl, Phaedromus serenades the door (Song #2). When Planesium emerges, the two lovers have a touching encounter, which Palinurus gruffly breaks up. As Planesium hurries back into Cappadox’s house, four prophetic chefs appear; they are to cook lunch for the parasite, who is due to return from Caria that very day. The young man, his slave, and the chefs all enter Phaedromus’ house.

Scenes 4-6: Cappadox and his four nurses emerge from the temple of Aesculapius, where the slave-dealer has spent the night (Song #3). Out of Phaedromus’ house comes Palinurus, who volunteers to interpret a bad dream that Cappadox has had; the prophetic chefs appear and send Palinurus away. They advise Cappadox to go back into the temple and make peace with the god. Palinurus returns, sees Curculio arriving, and calls Phaedromus outside. The hungry parasite announces that he was not able to get any money but did steal the signet ring of a soldier, Therapontigonus Platagidorus, who was intending to buy Planesium for himself and had left money for that purpose with a banker in Epidaurus. Curculio plans to forge a letter, seal it with the ring, pretend to be a messenger from the soldier, and convince the slave-dealer to sell Planesium to him instead of the soldier. He and the others go inside the house to make preparations.

Scenes 7-9: Lyco the banker arrives with his apprentices and complains about being broke (Song #4). Accosted by the disguised Curculio, he is suspicious but in the end falls for the fake letter and agrees to give the soldier’s money to Cappadox, who just then comes out of the temple with his nurses; as he, Lyco, and Curculio go into his house to finalize the deal, the nurses sing about their occupational woes (Song #5). Curculio, Cappadox, and Lyco emerge with Planesium. Warning the slave-dealer that he will have to return the money if the girl is ever found to be free-born, Curculio leads her away–ostensibly to the soldier but actually to Phaedromus’ house. Lyco departs; Cappadox goes back into the temple again, this time to thank the god for a profitable day.

Plautus Pseudolus Summary

Scenes 10-14: Therapontigonus enters with Lyco, whom he has run into and from whom he demands his money so that he can buy Planesium. Lyco leaves, insisting that the deal is already done. Cappadox exits from the temple; Therapontigonus learns from him what has happened and rightly assumes that the culprit is Curculio. Cappadox leaves to find the banker as Curculio, Phaedromus, and Planesium rush out of the house. After an animated conversation, Therapontigonus discovers that Planesium is his long-lost sister (Song #6). As he gladly betroths her to Phaedromus, Cappadox returns and is forced to pay back all the money he received for the free-born girl. The play ends on a happy note.

Home | Conclusion | Return to CLA 220 | Return to Cornell College |

| Old Comedies Aristophanes' Clouds | The Comedies of Menander | Plautus's Pseudolus |

FilmsThe Comedies of Charlie Chaplin | Frank Capra's It Happened One Night | The Marx Brother's A Night at the Opera |

Plautus's Pseudolus

As in both the plays of Aristophanes and Menander, the roman playwright Plautus addresses the issues of class consciousness and status in his works. Plautus particularly addresses the influence that class and status had on ancient Roman society and thinking. This is clear throughout his play, Pseudolus, in which each of the characters are developed based on their class and status. Their actions are reflections of how the issues of class, wealth, and status influenced Plautus, and, through his plays, influenced Roman society.

Lower Class -

Pot Of Gold Plautus Summary

Pseudolus

Pseudolus is the main character of the play, and, as a slave, represents a low social status in Roman society. He is cunning and is against authority, even his own master:

SIMO: His words will now convince you that you've taken on / not Pseudolus, but Socrates.

PSEUD: All right. I realize you've always put me down; / I know you've got no confidence in me. / You'd like me worthless; still, I'll be first class.

SIMO: Keep your ear space vacant, Pseudolus; / Admit my words as tenants for a while.

PSEUD: Speak your mind, though I'm furious at you.

SIMO: A slave, furious at me, your master?

PSEUD: Does that / Seem so strange? (464-472)

Unlike the lower class characters in Aristophanes' plays, Pseudolus seems to be his own master. He is the star of the play. This is in contrast to the main characters of Aristophanes' plays who, while being of lower classes, are far above slaves on the social ladder. Pseudolus represents an attack on the upper class, because, although he is a slave, he is more cunning than they, and can manipulate them:

He's gone; you're on your own now, Pseudolus. / Now what'll you do? You've loaded master's son / With precious promises; can you get the goods? / If you haven't a particle of a proper plan / You can't begin to weave a cunning cloth / Or execute a definite design. / But look at the poet: when he starts to write, / He seeks was doesn't exist, and the he finds it; / He makes invented fiction look like truth. / All right, I'll be a poet! Twenty coins, / Which don't exist on the face of the earth, I'll find. / Ages ago I said I'd give him [Calidorus] the money, / Hoping to lay a snare for our old man ; but somehow 'Dad' [Simo] got wind of what I wanted. (394-408)

For all that he is a trickster, Pseudolus does not manipulate the upper classes for his own advancement. He does it to help others, although often twisting his plans to benefit himself at the same time. Pseudolus offers to help Calidorus find the money to keep his girlfriend by saying, 'Don't fear, my lovesick dear, I won't desert you. / Somewhere, somehow, some way (maybe) today / I'll find you silvery succor and salvation. / Where, oh where will it come from? I don't know, / But I know it will: I've got a twitching brow' (103-107).

Plautus uses Pseudolus as a means of creating a comic hero whose worth is not based on his status and class in society. Instead his worth is based on his ruthless cunning and his kindness to those he helps. While it is clear that Pseudolus is a slave, it is also clear that he is has to potential to be kind and helpful to those he cares about. Plautus was attempting to show his audience that human worth is not based merely on wealth and social position, but on decent human qualities that transcend what society dictates as making a human powerful and great. Pseudolus is not of a powerful status, but his intelligence and kindness to those he loves makes him a great and essentially good character.

Upper Class -

Calidorus

Calidorus is the son of Pseudolus' master, and he is a lovesick and naïve young man. Calidorus represents the higher class, which should put him in a position of power, but he immediately defers his problem to Pseudolus and becomes dependent on the slave: 'Help me: what should I send this man / To stop my girl from going on sale?' (233-234). He even lets Pseudolus boss him around:

CALID: I'm tortured!

PSEUD: Toughen up!

CALID: I can't.

PSEUD: Well, force yourself!

CALID: How can I?

PSEUD: Try to control your emotions, man! / Concentrate on constructive thoughts; / When things go wrong, don't pander to passion . . . CALID: Pseudolus, let me be silly. Please!

PSEUD: I'll let you, if you let me leave.

CALID: Wait! Wait! I'll be just the way you want me.

PSEUD: Now you're sounding sensible. (236-241)

While Calidorus is of a higher class, he has little power. He depends on Pseudolus, and is unable to stand up against Ballio by himself. He even asks Pseudolus to begin insulting Ballio, rather than start it on his own: 'Pseudolus, stand on the other side and pile curses on him [Ballio]' (358-359). He cannot fight his own battles.

Plautus uses Calidorus' character to show that wealth and high class does not necessarily go along with power. While the powerful may often be wealthy, the wealthy may not always be powerful. Plautus was trying to make a statement about judging a person based merely on wealth and class. Calidorus is likable and his whining adds a lot of comedy to the play, but he is not an influential character. He is a key role, but is never a driving force behind the action.

High Status -

Ballio

Ballio is a wealthy slave dealer and pimp, and is the villain of he play. He is manipulative, and is in a position of power over his slaves:

Get out! Come on, get out, you slugs! / As merchandise you're rotten; / You never do no good nohow: / There's naught you've not forgotten! / Unless I whip you this way, / You aren't in the least bit useful; / You're more like donkeys than men, / With ribs all striped and bruiseful. (133-137)

He is also in a position of power over Calidorus, who is of a higher class, but is unable to stand up to Ballio's villainous double-dealing:

CALID: What do you say, you ultimate / Extreme of human perjury? / Did you swear that you would never / Sell her to anyone but me?

BALLIO: I did, and I admit it.

CALID: Well then. / Hadn't you pledged, and formally too?

BALLIO: Yes, but I fudged; I normally do.

CALID: Perjury! You criminal!

BALLIO: I put some money in my pocket. / If that's criminal, don't knock it. / You've got virtue and family fame- / But not a penny to your name. (351-357)

While Ballio is wealthy and powerful, he is not at all likable. Plautus uses him as an example of how wealth and power have to potential to corrupt. While Calidorus is wealthy but not powerful, he is likable. Pseudolus is not wealthy nor of high class, but he is in a position of power and is the hero of the play. Ballio, on the other hand, is wealthy and powerful but detestable. While he meets the generally accepted criteria for greatness, wealth and power, no person would ever call Ballio a great man. Plautus uses this as a means of showing society how little wealth and power count towards true human worth.

Upper Class -

Simo

Simo, a wealthy slave owner, is the master of Pseudolus, so he should be in the position of power. However, Pseudolus once again gets the upper hand when the slave tricks Simo into making a bet that Pseudolus is already sure that he will win:

PSEUD: Ye gods! I'll never beg from another man / While you're alive. You'll give the cash yourself./ I'll wheedle it from you.

SIMO: From me?

PSEUD: Precisely.

SIMO: Holy Herc, knock out my eye, if I give.

PSEUD: You'll give. / Watch out; you've got fair warning. (507-510)

Simo plays the role of the upper class man who is somehow tricked into losing money to a poor, cunning slave. Although, he still has the power to deny Pseudolus the bet money, but he does not because he is dignified and keeps his promises: 'I'll go inside / To find the twenty minas/ that I promised if he did the job. / I'll pay him of my own free will. / The creature is so very clever, / Very cunning, very sly./ Pseudolus has quite surpassed/ The Trojan horse, Ulysses too' (1240-1244). Finally by the end of the play, Simo and Pseudolus are closer to equals in terms of their power: Pseudolus has won the bet by outsmarting his master, yet Simo is fair and fulfills his end of the bargain.

| Old Comedies Aristophanes' Clouds | The Comedies of Menander | Plautus's Pseudolus |

| FilmsThe Comedies of Charlie Chaplin | Frank Capra's It Happened One Night | The Marx Brother's A Night at the Opera |

Home | Conclusion | Return to CLA 220 | Return to Cornell College |